So Life-like: Hair Loss is a Problem That’s More than Skin Deep

Scottsdale Progress May 4, 1991For example, take the man who used snake oil to try stimulate hair growth: or the one that bounced airwaves off his head to do the same; or the one that had arteries on the top and sides of his head cut because someone told him it would generate growth.

Then there are those that cover up the problem, such as the guy who took three hours every morning to comb the fringe he had left up over the top of his head, weaving it together to stay and cementing it in place with hair spray; or the guy who similarly took hair from one side of his head and combed it all the way over the top to the other side.

These cases and more than 2,500 others from all over the world have wound up in the office of Dr. Shelly A. Friedman, a Scottsdale dermatologist who specializes in hair transplants.

“It’s sad; it really is sad,” Friedman said recently. “That’s what men go through.”

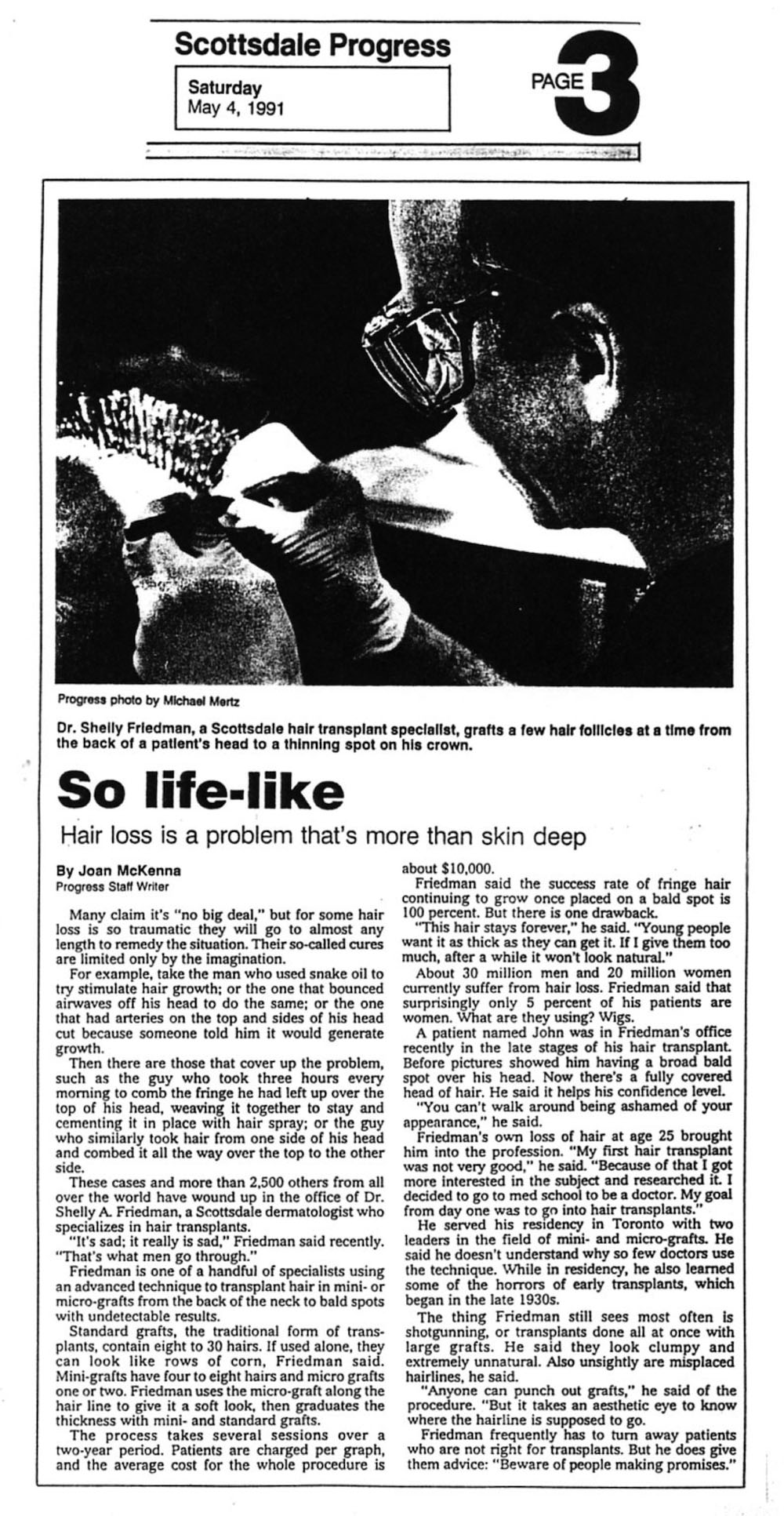

Friedman is one of a handful of specialists using an advanced technique to transplant hair in mini- or micro-grafts from the back of the neck to bald spots with undetectable results.

Standard grafts, the traditional form of transplants, contain eight to 30 hairs. If used alone, they can look like rows of corn, Friedman said. Mini-grafts have four to eight hairs and micro-grafts one or two. Friedman uses the micro-graft along the hair line to give it a soft look, then graduates the thickness with mini- and standard grafts.

The process takes several sessions over a two-year period. Patients are charged per graph, and the average cost for the whole procedure is about $10,000.

Friedman said the success rate of fringe hair continuing to grow once placed on a bald spot is 100 percent. But there is one drawback.

“This hair stays forever,” he said. “Young people want it as thick as they can get it. If I give them too much, after a while it won’t look natural.”

About 30 million men and 20 million women currently suffer from hair loss. Friedman said that surprisingly only 5 percent of his patients are women. What are they using? Wigs.

A patient named John was in Friedman’s office recently in the late stages of his hair transplant. Before pictures showed him having a broad bald spot over his head. Now there’s a fully covered head o! hair. He said it helps his confidence level.

“You can’t walk around being ashamed of your appearance,” he said.

Friedman’s own loss of hair at age 25 brought him into the profession. “My first hair transplant was not very good.” he said. “Because of that I got more interested in the subject and researched it. I decided to go to med school to be a doctor. My goal from day one was to go into hair transplants.”

He served his residency in Toronto with two leaders in the field of mini- and micro-grafts. He said he doesn’t understand why so few doctors use the technique. While in residency, he also learned some of the horrors of early transplants, which began in the late 1930s.

The thing Friedman still sees most often is shotgunning, or transplants done all at once with large grafts. He said they look clumpy and extremely unnatural. Also unsightly are misplaced hairlines, he said.

“Anyone can punch out grafts,” he said of the procedure. “But it takes an aesthetic eye to know where the hairline is supposed to go.”

Friedman frequently has to turn away patients who are not right for transplants. But he does give them advice: “Beware of people making promises.”